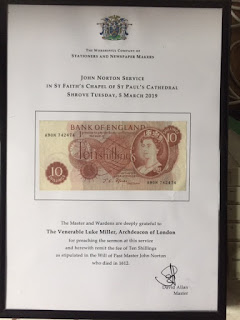

Norton Sermon

This annual sermon was instituted in the will of John Norton, d 1612 to be preached annually at the beginning of Lent in S Paul's Cathedral.

Readings 1 Kngs 19:1-9 Matthew 9:14-19

We began

with the Elgar Ave Verum Corpus sung so brilliantly by the choir of the Stationers' Crown Woods Academy. John

Norton was granted the office of King's Printer in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew in

1603, following the accession of James I. Norton, a Shropshire man who

started out in the printing and book trade in Edinburgh, was a great supporter

of the new King. Indeed he was probably involved in the machinations behind the

scenes in 1601 to ensure that James would succeed Elizabeth I, and in 1603 his

press in London rushed out James’s manifesto on good government, Basilikon Doron selling thousands of

copies in London before the King himself arrived in the south. In this Norton

demonstrated the development of his business: the first Edinburgh edition of

1599 sold just seven copies.

Now the

point of all this history is to set the scene of a man who understood not only

business but the cultural issues of high politics. Like Elijah he was involved

at court and mixed up with government; and like Elijah the reason for this was

that wise government, whether it is good or bad - and whatever you think of

James I & VI, the government of Ahab and Jezebel was pretty bad – wise

government looks to ideas and culture as much as to blunt power and economics.

And at the heart of cultural or intellectual life lies religion and faith. Even

if it is rejected, faith is there, and must be grappled with, engaged and

considered. So much of the failure of our modern politics is in its inability

to ‘do religion.’

Now this is

a sermon and not a history lecture, so although it is all about cultural and

religious politics, we must have another occasion to consider the fascinating

story of John Norton’s work in the international book trade and his negotiationwith Bodley to establish the copyright libraries which would acquire and make

available the books – often banned in England - that would be needed for the

academic polemic of the counter reformation. We must also leave aside his other

publishing feats of the period leading up Norton’s death in 1612, which may

have been brought on by the stress involved in the publication of the King’s

Authorised Bible in 1611 from which we have just read. So Stationers - be careful when you pick up a Bible: it might kill you. Or give you life!

Norton got

the importance of the spiritual. But his will mixed the materialistic with the

spiritual. The provision of cake and ale following the preaching of a sermon.

This may seem to run entirely counter to his intellectual activity, but in fact

it was of a piece with his Christianity. Christianity is the most materialistic

of religions, more so perhaps even than Judaism. Elijah’s encounter with theLord is mediated through water and cakes. At the low point of his career he

flees from Ahab and Jezebel into the wilderness and there prays for death. The

Lord’s response is not to persuade him, nor to give him a change of heart, but

to provide food and drink. And on the strength of that food he went 40 days,

fasting and travelling towards a further encounter with God.

Christians

encounter God in food: in bread and wine, his body and blood which Christ gives

to his children. The jug of water and the baked cake were and anticipation, a

type, of the true body, the verum corpus,

born of Mary. Food by which God does more than give us encouragement, but

unites us to himself not just by means of spiritual experience, but by physical

encounter.

Norton

understood this. Human beings are not spirits trapped inside bodies, but

unified beings, body and soul. I have a sermon in which I hold up the picture

of a 10-year-old boy and talk about how his mother is bereaved of him but has

nowhere to go to mourn for him; he has no grave. If his mother would have a

place to express the sorrow for her child she must come to me, for the picture

is my school photograph. Because we live in the world of time I do not yet know

what it is to be fully myself, for I can only be what I am now. In the

resurrection everything that my body has made me, everything that my spirit and

intellect have been, are taken and consummated and perfected such that the

child I was and the man I am, and the geriatric I may become, will all at once

be present, and at last I shall be complete and whole.

Which is why

we fast. Jesus said that his disciples would fast and we do so, giving up

things which are good in themselves in order that we may no longer take them

for granted, but develop a spirit of Thanksgiving. We fast also that we might

depend upon God and not upon any human addiction: For if we cannot give

something up then we are addicted to it. We fast that we may train in living obediently and dutifully towards God; and we fast from things in order that

we may give them to God in sacrifice, not holding them for ourselves but

developing a spirit of generosity. For this last reason we develop our

philanthropy more fully during Lent and take up extra good deeds while at the

same time letting go of the things which distract us from the service of God, our sins.

Thus

profoundly our spiritual lives are fed and grow as a result of our material

actions.

As we all

know John Norton established this sermon and the feast which goes with it for

Ash Wednesday. But I suggest he did not do so in order to undermine the

purposes for which fasting is given, nor would he have rejected the fast which

Christ himself enjoins on his followers. What he sought was an end to perceived

abuses of fasting by which one might misunderstand the fast as some kind of

work in response to which God would give a reward.

Good

Protestant stuff; but the protestation of our age is not against misuse of

fasting but against ungratefulness; addiction; abuse; gluttony; avarice; disobedience; selfishness (did you know more people die of obesity in our world than a

famine)? You do not need to believe in God for these to be bad or to wish to

work against them. But if like John Norton you do protest against them within

the context of the Christian faith, then surely it is right that we should use

fasting correctly, feasting today and taking Lent seriously from tomorrow.

This is

surely one of those instances where the change of tradition in fact upholds

what traditionally it has been sought to achieve. So feast today; and on the

strength of this food go forward 40 days into the wilderness of Lent. But on

that journey look forward to greeting the Lord when he shall reveal himself to us in a cave, not dead but living.

Comments

Post a Comment